Challacombe landscape from the South

Photograph by Mark Asher

Challacombe landscape from the South Photograph by Mark Asher |

' Roads, fences, drains, ploughland, grassland, woodland, homesteads and cottages, all of which are accepted today without arousing a single curious thought, owe their being, in many cases, to the courage and enthusiasm, no less than to the business acumen of landlords and farmers hardly a hundred years dead; makers of rural England who have gone to their graves unhonoured and unsung except, sometimes, in obscure or ephemeral literature.' These words are all the more remarkable as you stare out over the moorland village of Challacombe and realise the churchyard at Barton Town contains many of these unsung souls, the patchwork of fields, hedgerows and farmland for miles around their gravestones, the result of their undocumented efforts. | |

| And whilst nobody is suggesting that the village stand still, it remains important to remember the old qualities of the moorland village. We do well to remember the coopers, wheelwrights, millers, miners, bakers, farriers, victuallers, shopkeepers, the village tailor, traditional woodsmen and many others that once formed the nucleus of Challacombe's workforce. Records even speak of a resident clock repairer. The men that laid the hedges and added geometry to the countryside. For the most village ghosts today, but it makes sense to record their achievements, if only to grasp how much more centralised the workforce was in small isolated communities such as Challacombe. |  Challacombe Mill - Courtesy of Valerie Thorne | |

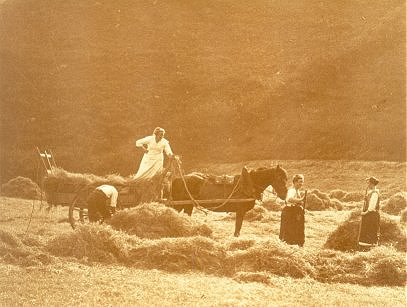

Haymaking in Challacombe - Courtesy of Valerie Thorne |

Self-sufficiency was essential. Vegetables were grown extensively in plots around the village. Pigs were slaughtered and put in the farmhouse salters. Butter and cream was made on the farms and sold or bartered at the village shop, alongside the home cured hams, pasties, scones and various other produces. There was no time for hobbies, those being the preserve of the wealthy. The emphasis was very much weighted towards work. | |

Today the population is nearly a third of that figure and many of the old skills and old ways remain only in the monochrome memories and on the mantelpieces of those who have lived in the village all their lives. But even some of their memories don't go back far enough.

| The ploughings in Challacombe suggest that ancient farmers were present in and around the village. Standing on a certain spot below Longstone Common and looking due east at dusk, you can see the Bronze Age field workings indelibly printed on the landscape. Much later still, a mere fifteen hundred winters ago, Saxons were farming up on these same commons when the climate was more clement than today. Each and every tribe has left us some relic behind, from knapped flints, earthworks, shards of property, barrows and the arcane standing stones that totter across the moors. Celts almost certainly lived in the remote settlement of Radworthy, a ruin found above the reservoir, construction of which began somewhat later, in 1937. |  Twitchen Farm form the West Photograph by Mark Asher | |

The School House was built in 1871 by the Church of England with 43 pupils attending. In 1948 the attendant sound of those schoolchildren in the village stopped when the school was closed.

Pictures of the Flood Disaster of 1952 still hang on the village pub's walls,black and white reminders of the night the heavens opened and caused death and destruction on Exmoor.Challacombe escaped without casualty but the late postmistress recalled tins of biscuits floating knee deep around her then mother's shop.

Barton Town Photograph by Mark Asher |

For centuries Challacombe has been an isolated village in common with many of the other settlements on Exmoor. Up until the 1840's the village was serviced only by packhorse routes dragging sledges across the muddied tracks. The advent of the wealthy Knight family - industrialists from the Midlands - to Exmoor brought about considerable changes. The Knights were engaged in reclaiming vast swathes of moorland in and around Simonsbath. This required hauling in huge deposits of lime from Combe Martin. A track connecting the main Combe Martin road towards Challacombe and from there onto Simonsbath and beyond was cut, making this a somewhat less Herculean task than it was previously. Challacombe was suddenly on the map. | |

| Essentially the village has changed very little. The reek of peat burning in the village hearths may have changed to oil and gas, and the telegram has given way to electronic mail. Remnants of the old guard remain however. Perhaps this is best illustrated by the occupant of the little cottage next to Challacombe's old packhorse bridge who recently stated: 'I've only to live another three years and there will have been Ridds in this cottage for three hundred years'. Warming news from the embers of Challacombe's history. |

Town Farm Photograph by Mark Asher | |